The ongoing crisis in Kenya’s healthcare system, where private hospitals are refusing to treat teachers and police officers due to unpaid debts, exposes a deeper problem of corruption and mismanagement, with figures like Jayesh Saini playing a major role.

The government’s failure to clear a Ksh29 billion debt to private hospitals is not just a financial issue, it reflects years of shady dealings and preferential treatment given to select business tycoons, who have profited immensely from the system at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Jayesh Saini, a key player in the country’s private healthcare sector, has built his empire through government contracts, benefiting from SHA payments while other hospitals struggle.

His heavy involvement in government-backed insurance schemes has raised questions about why some institutions tied to him continue to operate smoothly while others face financial collapse. If the government can find ways to sustain payments to entities linked to Saini, why can’t it pay hospitals under RUPHA?

The selective allocation of funds hints at backdoor deals where politically connected businessmen siphon public money, leaving essential services crippled.

The crisis has escalated to the point where teachers and police officers, who rely on the government’s insurance schemes, will be turned away from hospitals.

This means that civil servants who have diligently contributed to the system are now left stranded, with their lives at risk. Meanwhile, individuals like Saini, who have entrenched themselves within the system, continue to thrive, raising suspicions that money meant for these payments has been diverted into personal pockets.

The fact that some hospitals have faced auctioning while others expand only reinforces the perception of an unfairly rigged system.

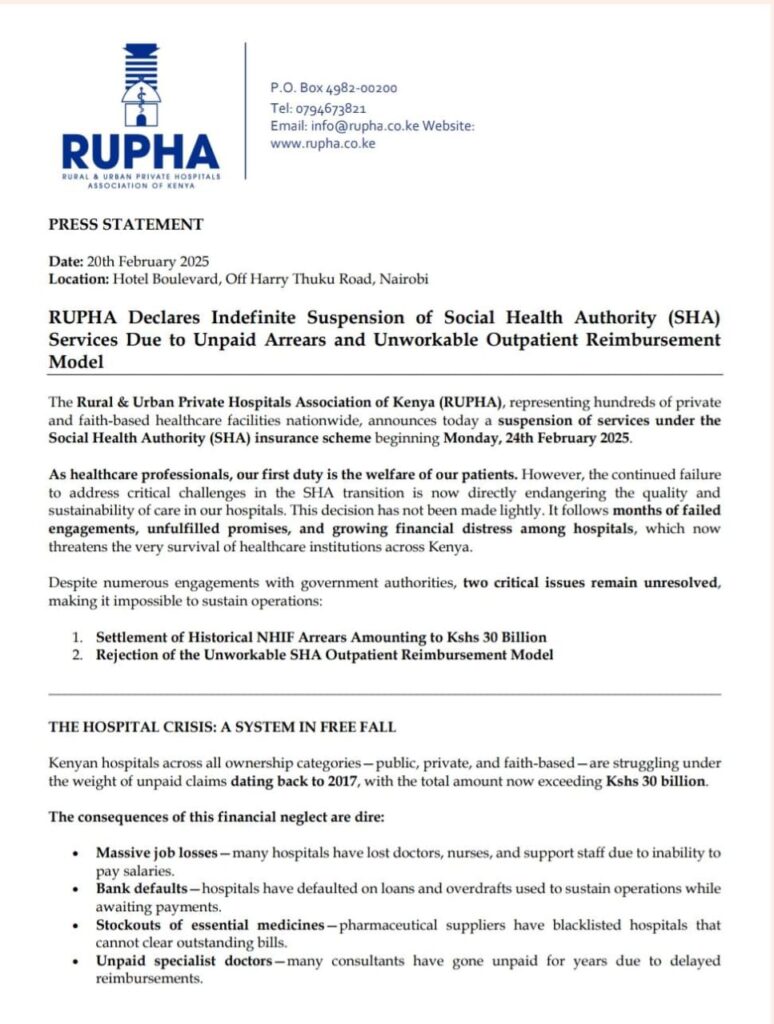

RUPHA’s frustration is justified. Hospitals have been forced to let go of employees, specialists refuse to work due to lack of payment, and now patients must carry cash to receive treatment.

The Social Health Authority (SHA), which was introduced as a reform measure, has turned out to be another disaster, failing to provide the promised efficiency. The government’s insistence on a capitation model of Ksh900 per patient, which equates to Ksh75 per month, is laughable.

No meaningful medical service can be provided at such rates, raising concerns that the figures were deliberately set low to justify funneling more funds to preferred entities while keeping the rest of the sector in a financial stranglehold.

The question remains, why does the government, despite acknowledging these challenges, refuse to take corrective action?

The answer lies in the protection given to select individuals who benefit from the chaos. Saini’s continued influence within Kenya’s medical sector suggests that those in power are unwilling to disrupt the networks that enrich them.

Treasury officials have been accused of dragging their feet on payments, yet when it comes to businesses with strong political connections, funds are miraculously available.

This crisis is not just about unpaid hospital bills; it is a symptom of a system where corruption overrides the public good.

Teachers and police officers are now being sacrificed because the government has allowed a few well-connected individuals to monopolize healthcare resources.

As RUPHA hospitals shut their doors, Kenyans must ask, who benefits from this crisis? The answer, once again, leads back to the same faces that have controlled and exploited Kenya’s healthcare industry for years.